14 Apr The Children’s Rights Bill That Helped Give Young People A Voice

Scotland’s Youth MPs played a pivotal role in the Government unanimously voting to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) into law.

“If you rewind ten years, the bill wouldn’t have passed,” says Liam Fowley, Member of the Scottish Youth Parliament. “The vote marked the end of a two-decade long journey for the Scottish Youth Parliament. I may be biased, but we played a pretty big part in it.”

On 16 March, after decades of struggle, the Scottish Parliament unanimously voted to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) into law. The country became the first in the United Kingdom to do so. Incorporation means that all 45 rights within the Convention will become legally binding on Scotland’s public authorities, and they will be held accountable by the Government if the rights aren’t fulfilled. These rights include:

- Life, survival and development (Article 6)

- Protection from violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation (Articles 32-36)

- An education that enables children to fulfil their potential (Article 29)

- Express their opinions and be listened to (Article 12)

- Be able to enjoy play, leisure and culture (Article 31)

Though the Scottish Government’s UNCRC incorporation was announced in 2019, for Members of the Scottish Youth Parliament (MSYPs) the campaign to incorporate children’s rights into Scots law started much earlier. In 2017, they launched a national youth-led campaign called Right Here Right Now, which called for children’s rights to be incorporated into Scotland’s domestic law.

“We were able to say, ‘look what the young people of Scotland have done, this is our democratic mandate, young people in Scotland want this incorporated into Scots law’,” says Fowley. “When decision-makers hear directly from a majority of young people that they want something, it is impossible for them to [ignore]. Young people realise how important it is to have their rights cemented.”

Erin Campbell MSYP, Liam Fowley MSYP, Josh Kennedy MSYP

Left to right: Erin Campbell MSYP, Liam Fowley MSYP, Josh Kennedy MSYP (credit: EachOther/Josh Kennedy MSYP)

First ratified by the UK Government in 1991, the UNCRC established the right for young people to have their voice heard and their views taken seriously. This came at a time when young people in Scotland were demanding more agency. Eight years later, the Scottish Youth Parliament was launched in June 1999, on the premise of fulfilling Article 12 of the UNCRC, which is the right to be heard.

In April 2019, 20 years after the Scottish Youth Parliament was first established, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced plans to incorporate the UNCRC into Scots law within the next two years. This target was met by the Scottish Parliament on 16 March.

The diversity present within Scotland’s Youth MPs was a major part of the process. Of the 166 presently elected representatives, more than 14 percent are from minority ethnic groups, 10 percent higher than the average percentage of minority ethnic people in Scotland. Ranging from the ages of 14 to 25, 39 percent of Youth MPs in Scotland identify as LGBTQIIA+ while 9 percent are young carers and nearly 17 percent consider themselves to have a disability. “Scottish Youth Parliament has access to hundreds of young people at every school and education level and within every ethnic minority community,” says Fowley.

We were able to say, ‘look what the young people of Scotland have done, this is our democratic mandate, young people in Scotland want this incorporated into Scots law’.

– Liam Fowley MSYP

“The Scottish Youth Parliament was part of a network of people campaigning for the UNCRC’s incorporation and no one person was responsible,” Fowley says. The campaign gained national attention as Youth MPs contacted councillors, headteachers and Members of the Scottish Parliament [MSPs]. At any event, “the UNCRC became every Youth MPs elevator pitch or a part of their opening speech to raise awareness,” Fowley says. “Even in passing, young people would say, ‘have you heard about the UNCRC? Let’s catch up about it at lunch’.”

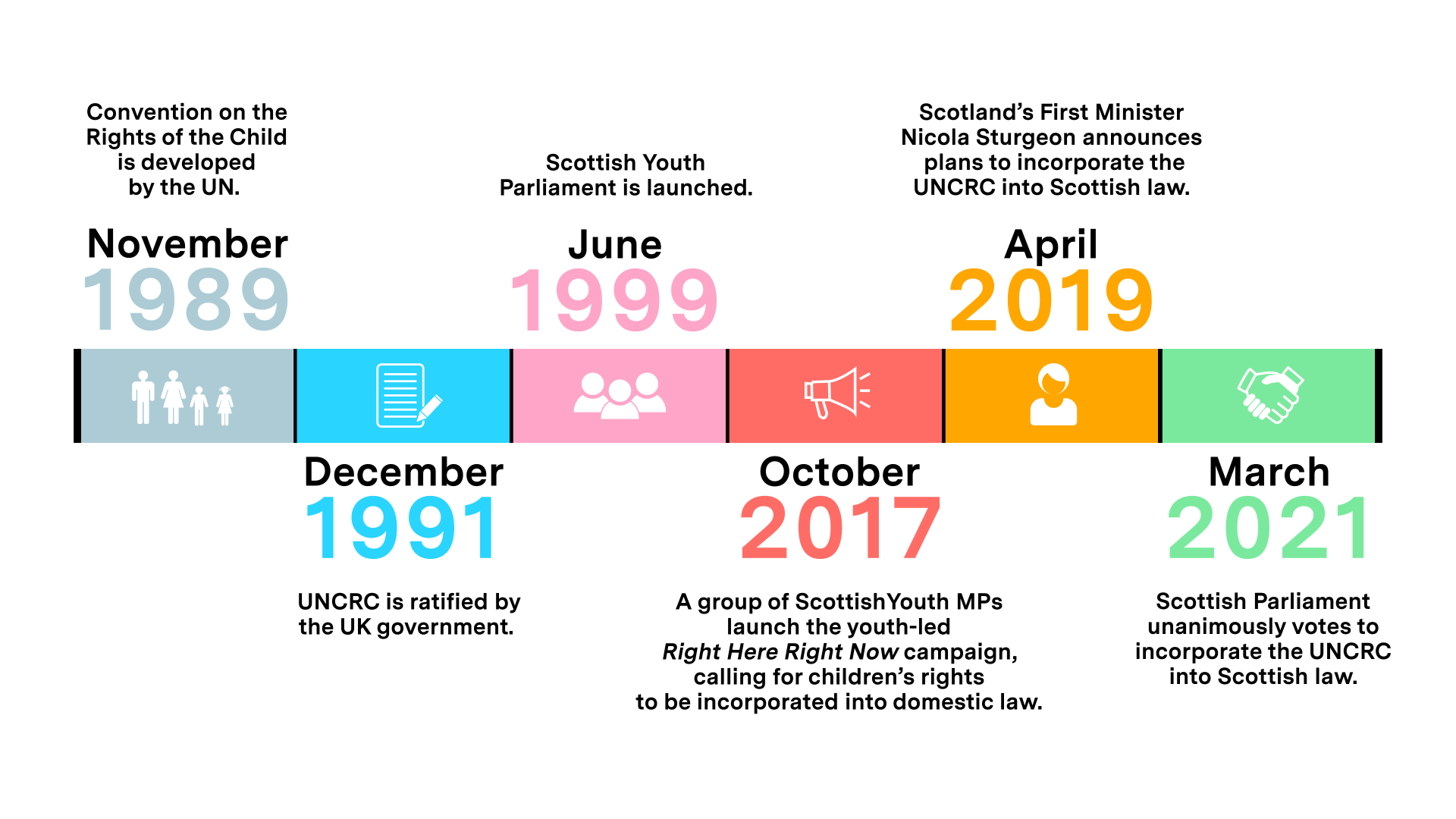

Timeline of the UNCRC implementation

A timeline outlining the journey towards Scotland’s UNCRC Bill implementation (credit: EachOther)

Gerry McMurtrie, who is Senior Professional Advisor at the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund UK (UNICEF UK) recalls that it was the children from “Rights Respecting Schools” operating an information stall at the Scottish Parliament that “really helped politicians see that the power of voice and knowing about your rights can change a person”.

UNICEF’s Rights Respecting Schools Award has worked alongside the Scottish Youth Parliament’s campaign to incorporate the UNCRC into Scots law. The award rewards a school’s achievement in putting the UNCRC into practice. The scheme was first introduced as a pilot in Scotland in 2010 and now more than 50 percent of all schools across Scotland are recognised as Rights Respecting Schools. “Even when young people have grown up and moved into the workplace, they know they have a right to have a say in decisions that have been made for them,” says McMurtrie.

“Article One of the UNCRC says that all rights are unconditional,” Josh Kennedy, Chair of the Scottish Youth Parliament, says. “I was told in school that in order to have rights, you must fulfil responsibilities first. That is a dangerous narrative. Talking through scenarios of when rights can be breached and what incorporation means was so important and interesting.”

Scottish Parliament (credit: EachOther)

Being involved in youth politics has also played a positive role in giving young people their voice. Both Erin Campbell MSYP and Josh Kennedy MSYP said that Article 12 of the UNCRC, the right to be heard, was the most important children’s right for them. “My confidence has grown since being a part of Scottish Youth Parliament,” says 17-year-old Campbell. “Two years ago, I couldn’t even be on the phone to someone, now I sit on the Board of Trustees.”

In 2011, Wales partially incorporated the UNCRC into Welsh domestic law by requiring Welsh ministers to consider the UNCRC when exercising any of their functions. However, the measure does not follow the model of incorporation recommended by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, because it does not ensure that children’s UNCRC rights can be enforced by the courts.

“I have been able to have a meeting with the First Minister about how the Government’s approach to the pandemic affects young people,” says former Welsh Youth MP Lloyd Mann. “But I absolutely think Wales should learn from Scottish Government’s actions [to fully incorporate the UNCRC].”

There’s no good news for children, the UNCRC (Incorporation) Bill is the good news.

-Dr Kasey McCall-Smith

However, the UK Government has raised concerns that threaten to stop the UNCRC from being incorporated into Scots law, and restrict young people’s right to be heard. On 24 March, Secretary of State for Scotland, Alister Jack, said that part of the bill “constrains the UK Parliament’s ability to make laws for Scotland” and that the “last resort” would be to take the case to the Supreme Court.

The UK Government’s constraint upon Scotland’s ability to incorporate the UNCRC bill raises a larger question as to why the UK Government hasn’t incorporated it into UK law. Jack said that protecting children’s rights is a “priority for the UK Government”, which signed up to the UNCRC in 1991. However, without incorporating the rights into UK law, there is a lack of “accountability and enforceability,” says Dr Kasey McCall-Smith, who served on the Expert Advisory Group on UNCRC incorporation in Scotland. “Even if Scotland’s Government wants to distance itself from the UK Government, using human rights as a means to do so, is not going to be bad for anybody.”

Still, the constitutional discussions between UK and Scottish devolved ministers is still in its early stages. “Sometimes individual states forge ahead with implementation as a way of distinguishing themselves,” says Professor Laura Lundy, who is Co-Director of the Centre for Children’s Rights at Queen’s University, Belfast. “The ‘peer pressure’ can encourage a race to the top or be met with resistance and Scotland’s bold move may generate both types of response.”

Group Scottish Youth MP photo

Scottish Youth MPs group photo (credit: Scottish Youth Parliament)

However, a report published by the Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE) in December 2020 shows that children’s rights have regressed in many areas since the UN’s last examination in 2016. It faces further threat from the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with Brexit. The report further showed that England was behind both Wales and Scotland, and the only country out of the three, without statutory obligations to conduct Child Rights Impact Assessments across departments. A lack of accountability among England’s public health authorities has played a role in the 4.2 million children living in poverty across the UK and 52 percent increase in child destitution since 2016.

The report also found that intersections between race and socio-economic conditions were negatively impacting those from Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, without any government strategy to address these intersections. Black children were found to be disproportionately represented in school exclusions and in all parts of the criminal system.

CRAE’s report, which was supported by more than 90 charities across England, calls for the UN to investigate the “worryingly low” state of children’s rights in the country. “This shows that UK law has not gone far enough,” says Dr McCall-Smith. “There’s no good news for children, the UNCRC (Incorporation) Bill is the good news.”

While the future of Scotland’s UNCRC (Incorporation) Bill hangs in the balance, the country’s young people played a pivotal role in driving it forward in a traditionally adult-dominated political arena. Their success will continue to empower young people across the UK to ensure they are taken seriously.